Courses & Projects by Rob Marano

CS 102 Weekly Course Notes

Week 1

1.0 — Course Introduction

This course guides you to learn how to use the programming languages of C and of Python 3 as tools to identify, formulate, and solve engineering problems using the priciples of mathematics, science, and engineering. At the end of this course, you will be able to apply engineering principles to produce software that meets specific needs, that is, you will know how to confidently write programs that achieve a certain goal at the necessary level of quality, e.g., program execution speed within the computer’s memory constraints as well as tested and documented for other engineers to understand, maintain, and expand functionality. Lastly, you will know how to test your software programs and verify their respective functionality with expected and unexpected inputs. As with all input to software, engineers expect outputs of a certain kind; so you will be able to visualize those outputs using ASCII characters on the console as well as graphs and charts using Python 3 libraries.

1.1 — Required course resources

- The C Programming Language, 2nd Edition by Brian W. Kernighan & Dennis M. Ritchie

- The official Python 3 Tutorial

1.2 — Know Thy Tools & Development Environment

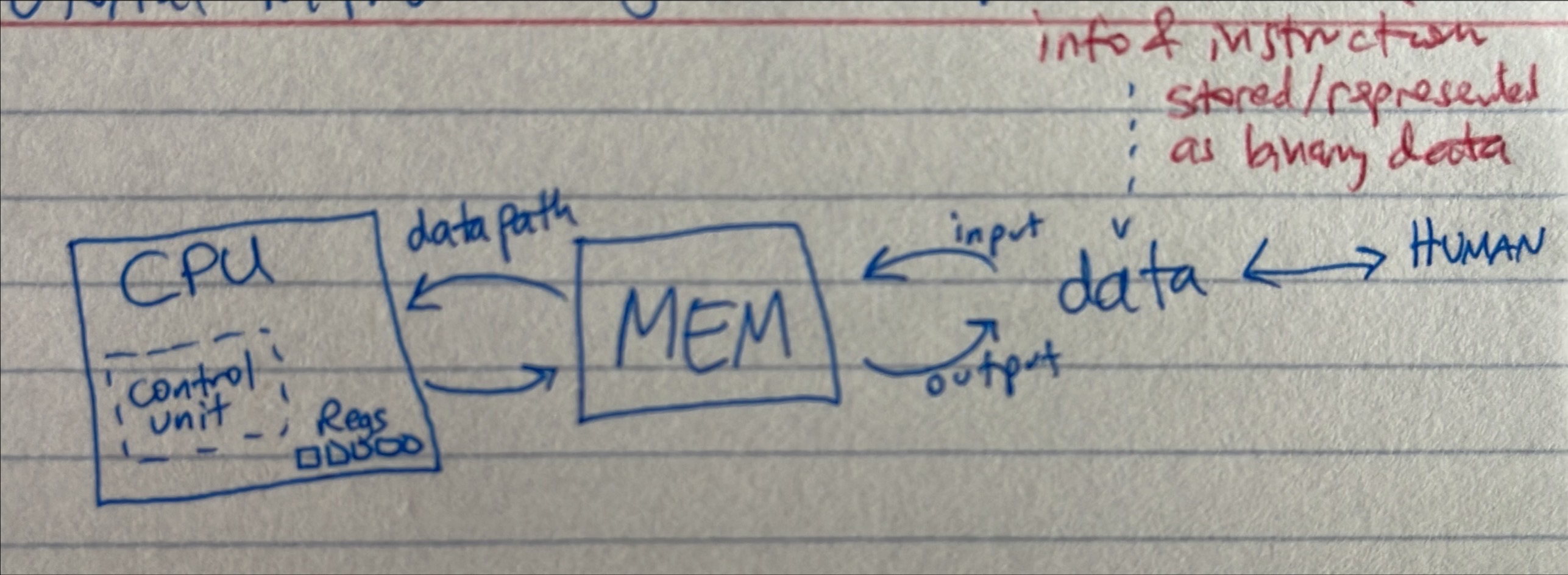

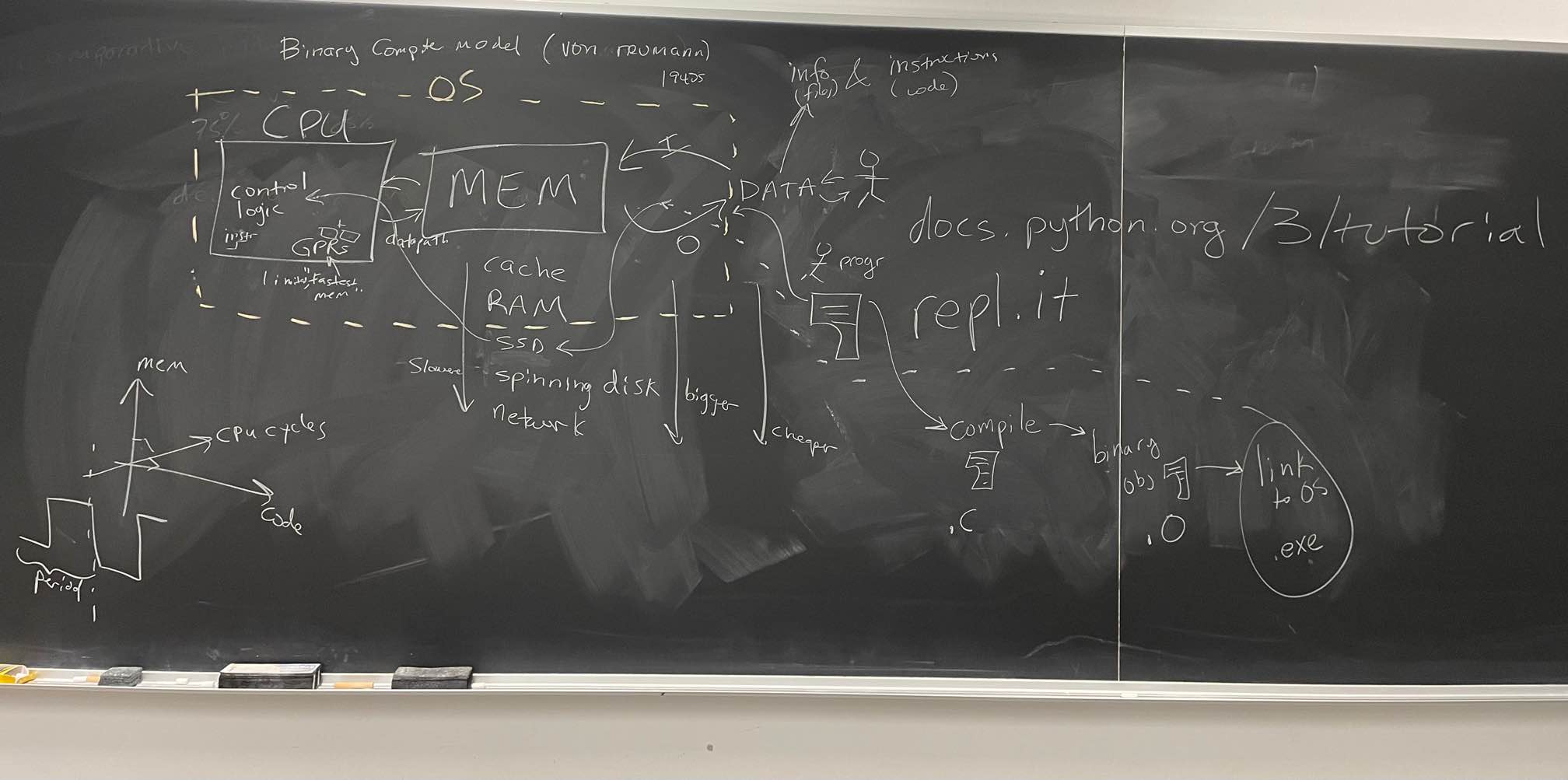

1.2.1 — The Computer (CPU + Memory <-> data)

The following is the von Neumann computer model that idealizes the modern digital computer and was postulated in the 1940s. Our modern digital computers (not the quantum ones) process logic using the binary number system, that is zero or one. Von Neumann’s stored-program concept states that instructions and the data upon which they operate are represented by binary digits (bits). Therefore, when looking at binary code (bits), one cannot tell if it is instructions or data. The first generation of these computers were programmed manually by humans who set memory locations either zero or one. The second generation generalized the electronic computing circuits into compute commands, e.g., MOVE, LOAD, STORE, ADD, etc. Humans did not have to program in bits but now in what we call assembly language, an imperative language. As computers became more popular, electronics miniaturized further, the computer field (computer science, computer architecture) advanced to ease the effort of programming computers as well as increased the quality of programs, such as, optimization of code to increase speed of execution as well as increase efficieny of using (fast) memory, a limited resource. In summary, machine code was the first generation of programming; assembly language as the second generation; and procedural languages are the third generation, e.g., COBOL, FORTRAN, ALGOL, PL/1, BASIC, C.

1.2.2 — The Bash Shell on Linux

The Linux operating system (OS) is the main program that runs on the computer (cs102.cooper.edu) and interfaces between you the user and the computer itself. The terminal (console) provides the command-line interface to the user to run programs. The Bash shell is the program that runs the terminal and provides console access to the user for input and for output. The EE Department’s Micro Lab staff have provided this presentation in PDF format to introduce how to use the Bash shell; here is the link to the document, and this link is a cheat sheet for the Bash shell.

1.2.3 — Text Editor

Since we will be working in the Linux terminal environment, let’s use vim, the text editor that usually ships with almost all Linux OSes. There are many tutorials on how to use vim, but here are two suggested ones:

When you’re developing on your own laptop or desktop computer, feel free to use a text editor like Sublime Text 3 or Microsoft Visual Code.

1.2.4 — Programming Paradigms

Computer scientists classify programming languages into many categories, based upon their respective functionality, e.g., how the code is organized, the execution model, style, syntax, or enabling side effects (modifying state variables values outside it local environment). In our course we will learn C and Python. These languages allow the programmer to instruct how the machine (computer) changes the state, i.e., the contents of a memory location. Memory can be a register, a cache location, a RAM address, a file in disk, etc. Computer science classifies C and Python as imperative programming paradigm. Subsets of imperative paradigms include but are not limited to procedural language and object oriented (OO). C is a procedural language, and so is Python 3, but the latter is also OO. C++, a superset of C, is OO. Procedural groups instructions into blocks, functions, or procedures (name depends upon the language history). OO groups instructions and state (memory) into units called classes, that are, in turn, instantiated into individal objects; for example, you can have a class called car, and an object for that class would be a Tesla X SUV. A class is like a cookie cutter template, and the object is the actual cookie you use, or eat. Declarative programming serves as another type of programming paradigm. With this classification, the language allows the programmer to declare the properties of the desired result after computation but not the logic of computation; SQL, HTML, CSS, XML serve as examples of declarative programming.

1.2.5 — Evaluating Performance of Programs

In computer architecture and computer science, we evaluate performance of a program for a traditional von Neumann computer by measuring the speed of execution and the consumption of memory — that which is needed and actually used. The number of instructions running on the CPU and the number of memory loads and stores determine the speed of the program. The efficiency of memory usage determines the consumption of memory used. Note that computers have a hierarchy of memory from fastest to slowest, registers then cache within the circuitry of the CPU to RAM (random access memory) connected to the CPU via a bus then to disk drives (SSD to spinning disks), then to other computers connected via a network. The former are more sparse and limited than the latter; that is, less registers than cache addresses, less cache locations than RAM addresses, less RAM locations than disk drive space, etc. So just remember that compute (logic and time) is one axis of performance, and memory (storage and space) is the other.

2.0 — Tutorial Introduction

Let’s get started with the mainline …

2.1 — C

The most rudimentary C program written into a file called hello1.c

/* This is a comment */

void main(void) {

return;

}

void is a type and think of it as “nothing.” main() is the name of the function or procedure of instructions encapsulated within the braces, this is { }. This pair of left- and right-braces forms a code block. Instructions within the code block run consecutively on the CPU, in general terms. This program enters main() and exits, or returns to the calling instruction, but what calls main()? The operating system (OS) calls the mainline. For programs running on Unix or Linux or Windows-based computers, the entry into an application is the mainline, i.e., main() — be the program written in C, Python, or any other programming language. Note the void`` that serves as the formal argument for the functionmain()``` means there are no formal arguments for this function.

The program in C needs to be converted to object code (machine code) then linked to the OS in order to be able to be run.

2.1.0 — Building (Compiling, Linking) and Executing

Working at the command-line interface (CLI) of Linux (on cs102.cooper.edu) and using the Bash shell environment:

$ cd $HOME

$ mkdir -p dev/cs102/week1

$ cd $HOME/dev/cs102/week1

$ vim hello1.c

Write the program above. Then …

$ gcc ./hello1.c

$ ls -la

drwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 4096 Sep 7 16:44 .

drwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 4096 Sep 7 16:43 ..

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 15768 Sep 7 16:44 a.out

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 29 Sep 7 16:44 hello1.c

Note the ./ in front of hello1.c means “in this directory, used the file ….”hello1.c”. The a.out is the executable file, or application. Usually in Windows, it ends in .exe, and in Linux it does not have an extension. For the course, we will always add the .exe extension manually when building. To confirm the type of the file,

$ file ./a.out

a.out: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=15c161dc7adde7d0a0161636a10ce8f5672a4e19, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

And to run, or execute, the application,

$ ./a.out

$

Notice there is not output seen. Why? Because there is no instruction other than return; in the C program. That means, return back to the calling function, which in this case is the OS kernel (master OS program which controls the CPU and memory). The OS, in turn, returns back to the shell, from which you called ./a.out.

Let’s now add the more normal Kernighan & Ritchie way of calling main()

in a file called hello2.c

/* This is a comment */

int main(void) {

return(0);

}

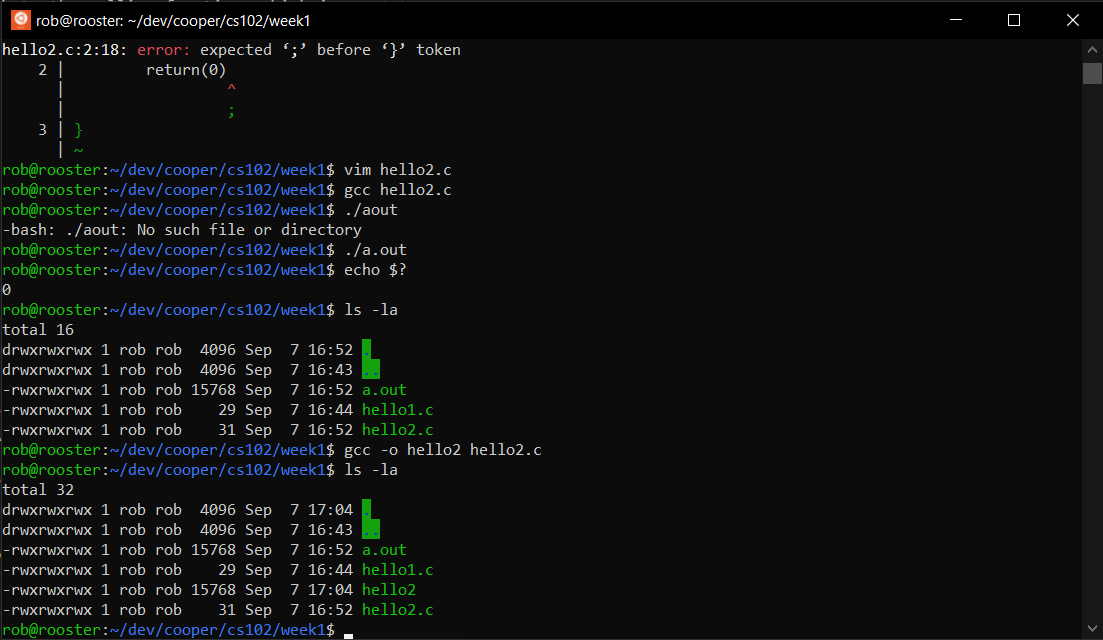

Let’s build the program (compile and link) by using the C compiler and linker called ```gcc`` or “the GNU C Compiler.”

$ gcc ./hello2.c

$ ./a.out

$ echo $?

0

This set of Bash shell commands compile and link the code file hello2.c to the executable program file a.out. Then the echo Bash shell command prints out the variable name $? which is the numeric value of the output of the last program or command run, in this case 0 or zero. And that is what we wanted; see the instruction return(0) from hello2.c. Mainline applications in CLI programs return a numeric result, where zero means success, and any other number means an error, which the programmer needs to explain through documentation. If you would like to jump ahead, this is a good tutorial on Linux C error handling, but caveat emptor, it’s advanced and may confuse you. We will cover later in the course.

Now, let’s give a good name to the executable program file that we build by using arguments of the C compiler. The argument -o followed by a term (“hello2”) means the application executable will be named that term.

$ gcc -o hello2 hello2.c

$ ls -la

drwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 4096 Sep 7 17:04 .

drwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 4096 Sep 7 16:43 ..

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 15768 Sep 7 16:52 a.out

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 29 Sep 7 16:44 hello1.c

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 15768 Sep 7 17:04 hello2

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rob rob 31 Sep 7 16:52 hello2.c

$ ./hello2

$ echo $?

0

Now let’s write the traditional, timeless introductory first C program:

in a file called hello3.c

#include <stdio.h>

/* main function */

int main(void) {

printf("Hello, World!\n");

return(0);

}

The function printf() allows the programmer to write to the console (or terminal) the (formatted) string declared as the formal argument. #include is a compiler directive that has the include file (any file ending .h in a C program) copied directly and replacing the line of the said include statement. Think of the include file as a separate file of instructions that you write once and reuse as you need, or share with other programmers. The console, also generally called the terminal screen, is the grid of slots where human readable characters are printed, see image below:

Build and execute the program:

$ gcc -o hello3 hello3.c

$ ./hello3

Hello, World!

$

Let’s make the string “Hello, World!\n” a symbolic constant named HELLO_STRING, in this first example use, we will use the compiler directive #define. The contents of the definition HELLO_STRING is placed wherever the symbolic constant is stated.

in a file called hello4.c

#include <stdio.h>

#define HELLO_STRING "Hello, World!\n"

/* main function */

int main(void) {

printf(HELLO_STRING);

return(0);

}

Build and execute the program:

$ gcc -o hello4 hello4.c

$ ./hello4

Hello, World!

$

2.2 — Python

Python unlike C is an interpreted imperative language. Behind the scenes, the Python source files (.py) are compiled to (.pyc) binary files after you run the Python interpreter on the file the first time. If you edit the source file, then the next time you run Python on that file, it will be recompiled to an updated .pyc binary Python file.

To run the Python interpreter at the CLI on Linux using the Bash shell. You issue the Python command exit() or Ctrl-d key sequence to exit the interpreter.

$ python

rob@rooster:~/dev/cooper/cs102/week1$ python3

Python 3.10.4 (main, Jun 29 2022, 12:14:53) [GCC 11.2.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> exit()

After the symbols >>>, you can issue Python source instructions, and after hitting enter, the Python interpreter will compile and execute your code. Note that running an interpreter like this does not store your files. Anything you write after the >>> is considered running in its mainline.

For example,

$ python

rob@rooster:~/dev/cooper/cs102/week1$ python3

Python 3.10.4 (main, Jun 29 2022, 12:14:53) [GCC 11.2.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> print('hello')

hello

>>> 1+1

2

>>> foo=1

>>> bar=2

>>> foo+bar

3

>>> print('Hello, World!\n')

Hello, World!

>>> print('Hello, World!')

Hello, World!

>>> exit()

Notice the slight difference in console, or terminal, formatting with the newline character \n between Python and C.

When you use the interpreter mode of Python, you do not save your work. Rather to write programs in Python you will write your source code in a set of files and execute the programs. We will write our programs for now in one file, until we get to writing modular code later in the course.

Write a simple Python “Hello World” program as we did in C with symbolic constant

in the source file python1.py

# This is a comment

# global area for the Python program

HELLO_STRING = 'Hello, World!'

# Mainline

if __name__ == '__main__':

print(HELLO_STRING)

Read Chapter 1 Sections 1.1 through 1.10 of the C textbook and the Python 3 tutorial Sections 1 through 3. Both these reading are a light introduction to each imperative programming language, and taken together are a comparative study.

Week 2 — Types, Operators, Expressions

1 — Lecture Materials

1.1 — Variable Names

In C

Variable names in C are composed of letters and numerals. The first character must always be a letter, lowercase or uppercase, and the names are case sensitive, that is, Variable differs from variable. The compiler treats an underscore (_) as a letter. Traditional C style guides reserve lowercase for variable names while all uppercase for symbolic constants, that is, those defined with the compiler directive #define.

In Python

According to the official Python Style Guide

Never use the characters ‘l’ (lowercase letter el), ‘O’ (uppercase letter oh), or ‘I’ (uppercase letter eye) as single character variable names. In some fonts, these characters are indistinguishable from the numerals one and zero. When tempted to use ‘l’, use ‘L’ instead. Function names should be lowercase, with words separated by underscores as necessary to improve readability. Variable names follow the same convention as function names. Constants are usually defined on a module level and written in all capital letters with underscores separating words. Examples include MAX_OVERFLOW and TOTAL. mixedCase is allowed only in contexts where that’s already the prevailing style (e.g. threading.py), to retain backwards compatibility.

1.2 — Data Types & Sizes

In C

C has a few, fundamental data types:

char— a single byte (8 bits), capable of storing one character in the local character set, e.g., ASCII. See ASCII table. A qualifier can precedecharas eitherunsignedorsigned, the latter is default when omitted.int— an integer, or whole number, typically reflecting the natural size of integers on the host machine, as defined by the instruction set architecture of the CPU, e.g., x86, x86_64, arm, or arm64. A qualifier can precedeintas eitherunsignedorsigned, the latter is default when omitted. Moreover,intcan further be defined as eithershortorlong. The instruction set architecture for the CPU determine the actual bit sizes for the combination ofint. Check this table for more details.float— single-precision floating point (real numbers as represented by the IEEE-754 standard).double— double-precision floating point.

See the Wikipedia entry on C data types for more information.

In Python

Python has several built-in data types, e.g., scalars (numeric and logical values) and complex structures (lists, dictionaries, and files).

Python Number Types

Python’s four number types include integers, floats, complex numbers, and Boolean

- integer : signed whole numbers (-15, 4, 29414225, -999999999999)

- float : signed real numbers (-15.2, 4.2, 2e7, -9e12, 6e-4)

- complex numbers : using

jinstead ofi(-4+2j, 6.22+94.3j) - Boolean : logical values (

True,False)

Python List Type

Python also has a built-in list type, unlike C. A list can contain a mixture of other types as its elements, e.g., strings (“character arrays”), tuples, lists, dictionaries, functions, file objects, and any number type. Lists are contained inside brackets, [ ].

For example:

[]— the empty list (meaning, it’s not null)[2][1,2,3,4,5]['one',1,5L,2.2,['c','u'], (12,32)]

List elements can be deferenced (accessed for value) using index values (indices).

For example, for the list my_list = [1,2,3,4] and len(my_list) (number of elements in ```my_list``) equals 4. Like C, Python deferences from the zeroth element, not the first. Below are examples of index and slice notation.

my_list[0]=my_list[-4]my_list[1]=my_list[-3]my_list[2]=my_list[-2]my_list[3]=my_list[-1]

Some built-in Python functions (len, max, min), some operators (in, +, *), the delete operator (del), and list methods (append, count, extend, index, insert, pop, remove, reverse, and sort) will operate on lists.

For example, using the Python interpreter at the CLI:

>>> x = [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

>>> len(x)

8

>>> [-2,-1] + x

[-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

>>> x.reverse()

>>> x

[7,6,5,4,3,2,1,0]

>>> x = [-2,-1] + x

>>> x

[-2,-1,7,6,5,4,3,2,1,0]

Note, the operators create new lists, leaving the original one intact. You need to remember to assign the new value to a variable name to keep in memory.

Python Tuple Type

Tuples are lists in Python but are immutable, that is, they cannot be modified after they are created. The built-in functions (len, max, min) and operators (in, +, *) function the same on tuples as they do on lists because none of these actions modify the original tuple/list. Tuples are contained inside parentheses, ( ). In its definition, the one-element tuple requires a comma, my_tuple = (5,). A frequent use of tuples is for use as keys in dictionaries. Also for performance reasons, you would use tuples when you want lists that are never modified. You can convert a list into a tuple with the operator tuple(), and a tuple can be converted into a list with the operator list(); for example:

>>> x = [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

>>> y = tuple(x)

>>> y

(0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7)

>>> z = list(y) + [8,9]

Python String Type

Strings and strings processing are part of Python’s strengths and hence popularity. A string in general is a list of human-readable characters, as in C. Strings are immutable, and as with lists, the built-in functions (len, max, min) and operators (in, +, *) as well as index and slice notation work the same as they do on lists and tuples.

Strings can be delimited by single ' ' or double " " or triple single ''' ''' or triple double """ """ quotes.

Python Dictionary Type

Python has a built-in data type for storing associations, that is, a dictionary, or a general list of key-value pairs. len function returns the number of key-value pairs in the dictionary, and del removes a key-value pair. As for the list type, the dictionary type has built-in methods, e.g., clear(), copy(), get(), has_key(), items(), keys(), update(), and values() to name a few popular ones.

>>> x = {1:'one', 2:'two'}

>>> x[1]

'one'

>>> list(x.keys())

[1,2]

>>> x.get(1, 'does not exist')

'one'

>>> x.get(0, 'does not exist')

'does not exist'

Python Set Type In Python a set is an unordered collection of values, that is, objects. This type in computer science is used when you seek to know membership and uniqueness of a set of values.

>>> x = [2,4,2,6,8,8,8,4]

>>> y = set(x)

>>> y

{8, 2, 4, 6}

>>> 5 in y

False

>>> 4 in y

True

As you can see, as compared to C, Python has a much deeper and wider collection of data types built-in and native.

1.3 — Constants

In C

There are several ways to define constants, that is, at compile time (building your program) and at run-time (execution of your program).

When building, you at the very least use compiler directive #define:

#include <stdio.h>

#define MY_CONSTANT_NUMBER 4.2

#define MY_CONSTANT_STRING "Hello, World!"

int main(void) {

printf("%f\n", MY_CONSTANT_NUMBER);

printf("%s\n", MY_CONSTANT_STRING);

return(0);

}

In Python

Constants in Python are usually declared and defined/assigned in Python module source code files. According to PEP8 — Style Guide for Python Code:

Constants are usually defined on a module level and written in all capital letters with underscores separating words. Examples include MAX_OVERFLOW and TOTAL.

We will discuss modules later in the semester.

1.4 — Declarations

Imperative programming languages require at least the definition of a variable for type. Interpreted languages like Python infer the type by the assigned value. Compiled languages like C require first the declaration of the variable type then its definition, or setting to a value.

In C

You must declare a variable’s data type, then you must define it.

/*

* variables_declared.c

*/

#include <stdio.h>

int a; /* this variable is global to the program, i.e., it's mainline */

int b = -2;

int main(void) {

int c; /* this variable is local to the code block in this function, the mainline */

a = 4;

printf("a = %d\n", a);

printf("b = %d\n", b);

b = b * 2;

printf("b = %d\n", b);

printf("c = %d\n", c);

c = a * b;

printf("c = %d\n", c);

return(0);

}

Now check at run-time:

$ gcc -o variables_declared.exe variables_declared.c

$ ./variables_declared.exe

a = 4

b = -2

b = -4

c = 213561440

c = -16

Note the first value printed for c before it was defined but after declared.

In Python

Since Python is an interpreted imperative language, running your Python code is always compile-time at run-time, that is, the source code is run everytime, so the interpreter parses the instructions, compiles then executes them. If there is no change to the source code, Python does save intermediate compiled object code to speed up execution. Constants in Python can be global or local (to a code block or function definition), in many ways like C. The global attribute that would be prepended to the declaration of a variable, making it a global variable to the entire execution of the program. The following is the source code stored in the file global_example.py:

#

# test.py

#

a = "one"

b = "two"

def my_func():

global a

a = 1

b = 2

return

# mainline of this Python program

if __name__ == '__main__':

print('a = {}'.format(a))

print('b = {}'.format(b))

my_func()

print('a = {}'.format(a))

print('b = {}'.format(b))

exit(0)

After executing this program, the output is:

$ python3 ./global_example.py

a = one

b = two

a = 1

b = two

$ echo $?

0

Since Python is interpreted, be attentive to where you declare and define your variables and which ones you truly want global.

1.5 — Arithmetic Operators

In both C and Python, you can manipulate each numeric value using arithmetic operators:

- addition :

+ - subtraction :

- - multiplication :

* - division :

/ - exponentiation :

** - modulus :

%

In C

In order or precedence from top to bottom from the list below:

| Operator | Description | Associates |

| —: | :— | :— |

| x[i], f(x) | array subscripting and function call | left to right |

| ., -> | direct and indirect structure field selection| left to right |

| x++,x-- | postfix increment / decrement operators | right to left |

| ++x, --x | prefix increment / decrement operators | right to left |

| sizeof,(< type >) | size of a variable or type (in bytes), cast to type | right to left |

| +,-,!,~ | unary plus, unary minus, logical and bitwise NOT operators | right to left |

| &,* | address of and dereferencing operators | right to left |

| *,/,% | multiply, divide, modulus | left to right |

| +,- | addition, subtraction | left to right |

| >>,<< | right, left bit shift | left to right |

| <,>,<=,>= | test for inequality | left to right |

| ==,!= | test for equality, inequality | left to right |

| & | bitwise AND | left to right |

| ^ | bitwise XOR (exclusive OR) | left to right |

| \| | bitwise OR (inclusive OR) | left to right |

| && | logical AND | left to right |

| \|\| | logical OR | left to right |

| ? : | conditional operator | right to left |

| = | variable assignment | right to left |

| +=,-=,*=,/=,%= | add to, subtract from, multiply to, divide from, assign remainder | right to left |

| <<=,>>=,^=,&=,\|= | shift right and left, assign bitwise XOR, AND, OR | right to left |

| , | sequential expresion evaluation | left to right |

In Python

In order or precedence from top to bottom from the list below:

| Operator | Description |

| —: | :— |

| (expressions...), [expressions...], {key: value...}, {expressions...}| Binding or parenthesized expression, list display, dictionary display, set display |

| x[index], x[index:index], x(arguments...), x.attribute | Subscription, slicing, call, attribute reference |

| await x | Await expression |

| ** | Exponentiation (the power operator ** binds less tightly than an arithmetic or bitwise unary operator on its right, that is, 2**-1 is 0.5.) |

| +x,-x,~x | Positive, negative, bitwise NOT |

| *,@,/,//,% | Multiplication, matrix multiplication, division, floor division, modulus/remainder |

| +,- | addition, subtraction |

| <<,>> | bitwise shift left, right |

| & | bitwise AND |

| ^ | bitwise XOR |

| \| | bitwise OR |

| in,not in,is,is not, <,<=,>,>=,!=,== | comparisons, including membership tests and identity tests |

| not x | boolean NOT |

| and | boolean AND |

| or | boolean OR |

| if - else | Conditional expression |

| lambda | Lambda expression |

| := | Assignment expression |

Week 3 — Types, Operators, Expressions (continued)

1 — Lecture Materials

1.0 — Inputting / Outputting

In C

Inputting from the user via the CLI terminal/console, one of the system functions to use is scanf(). Outputting, as you have already seen, can be done with one fo the system functions called printf() which means take the data and output to a file, one of which is STDOUT — a Unix/Linux file that prints to the teletypewriter (tty) called the terminal, or console.

Common formatting codes for reading and printing integers:

| Type | Reading with scanf() | Printing with printf() |

| —: | :— | :— |

| short | %hd or %hi | %d or %i |

| int | %d or %i | %d or %i |

| long | %ld or %li | %ld or %li |

| unsigned short | %hu | %u |

| unsigned int | %u | %u |

| unsigned long | %lu | %lu |

| octal short | %ho | %o |

| octal int | %o | %o |

| octal long | %lo | %lo |

| hex short | %hx | %x |

| hex int | %x | %x |

| hex long | %lx | %lx |

Input from the User

In C there are several options to have the computer take in the user’s input: getchar() and scanf().

```c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(void) {

int c;

printf("Type in characters on your keyboard.\n");

printf("Hit RETURN to repeat your typed line on the screen.\n");

printf("When you are done, type CTRL-D\n");

printf("If you type CTRL-C, the program immediately terminates.\n");

c = getchar();

/*

* On Linux systems and OS X, the character to input to cause an

* EOF is Ctrl-D. For Windows, it's Ctrl-Z.

* */

while (c != EOF) {

putchar(c);

c = getchar();

}

printf("You have typed CTRL-D.\nGoodbye!\n");

return(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

… ***

Week 11 — Putting it all together

Developing a C program from start to finish

We will create a new C program that hosts the game of tic-tac-toe.

Setting up a project’s collaborative source repository

Use the GitHub template repository called cs102-c-project-template.

For this course as discussed in detail in class, each student team will create their final C project source code repository from this GitHub Classroom link.

Using the template for your C program

Our template has main.c and main.h, and the Makefile compiles and links the object code into the tic-tac-toe executable program. In the next section, you will find the original code that Prof Carl Sable wrote to implement the tic-tac-toe computer game. Transform the code from one C source code into at least one C file and another header file.

Designing your C program from the top-down

/*

* This program plays Tic-Tac-Toe against the user!

* The program uses a specified, not-perfect strategy.

* The code uses only basic programming concepts.

* Written by: Carl Sable

*/

#include <stdio.h>

void init_board(void);

void draw_board(void);

int user_first(void);

int play_again(void);

int symbol_won(char);

int find_win(char);

int middle_open(void);

int find_corner(void);

int find_side(void);

void computer_move(void);

int square_valid(int);

void player_move(void);

void play_game(void);

char board[3][3];

char computer, user;

/*

* Initialize the board, ask who goes first, play a game,

* ask if user wants to play again.

*/

int main(void)

{

while(1)

{

init_board();

if (user_first())

{

computer = 'O';

user = 'X';

}

else

{

computer = 'X';

user = 'O';

}

play_game();

if (!play_again())

break;

}

return 0;

}

/* Make sure board starts off empty. */

void init_board(void)

{

int row, col;

for (row = 0; row < 3; row++)

for (col = 0; col < 3; col++)

board[row][col] = ' ';

return;

}

/* Display the board to standard output. */

void draw_board(void)

{

int row;

printf("\n");

for (row = 0; row < 3; row++)

{

printf(" * * \n");

printf(" %c * %c * %c \n",

board[row][0], board[row][1], board[row][2]);

printf(" * * \n");

if (row != 2)

printf("***********\n");

}

printf("\n");

return;

}

/*

* Ask if user wants to go first.

* Returns 1 if yes, 0 if no.

*/

int user_first(void)

{

char response;

printf("Do you want to go first? (y/n) ");

do

{

response = getchar();

} while ((response != 'y') && (response != 'Y') &&

(response != 'n') && (response != 'N'));

if ((response == 'y') || (response == 'Y'))

return 1;

else

return 0;

}

/*

* Ask if user wants to play again.

* Returns 1 if yes, 0 if no.

*/

int play_again(void)

{

char response;

printf("Do you want to play again? (y/n) ");

do

{

response = getchar();

} while ((response != 'y') && (response != 'Y') &&

(response != 'n') && (response != 'N'));

if ((response == 'y') || (response == 'Y'))

return 1;

else

return 0;

}

/*

* If middle square is empty, return 5;

* otherwise return 0.

*/

int middle_open(void)

{

if (board[1][1] == ' ')

return 5;

else

return 0;

}

/*

* Return the number of an empty corner, if one exists;

* otherwise return 0.

*/

int find_corner(void)

{

if (board[0][0] == ' ')

return 1;

if (board[0][2] == ' ')

return 3;

if (board[2][0] == ' ')

return 7;

if (board[2][2] == ' ')

return 9;

return 0;

}

/*

* Return the number of an empty side square, if one exists;

* otherwise return 0.

*/

int find_side(void)

{

if (board[0][1] == ' ')

return 2;

if (board[1][0] == ' ')

return 4;

if (board[1][2] == ' ')

return 6;

if (board[2][1] == ' ')

return 8;

return 0;

}

/* Check if the given square is valid and empty. */

int square_valid(int square)

{

int row, col;

row = (square - 1) / 3;

col = (square - 1) % 3;

if ((square >= 1) && (square <= 9))

{

if (board[row][col] == ' ')

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

/* Check if the given symbol has already won the game. */

int symbol_won(char symbol)

{

int row, col;

for (row = 0; row < 3; row++)

{

if ((board[row][0] == symbol) &&

(board[row][1] == symbol) &&

(board[row][2] == symbol))

return 1;

}

for (col = 0; col < 3; col++)

{

if ((board[0][col] == symbol) &&

(board[1][col] == symbol) &&

(board[2][col] == symbol))

return 1;

}

if ((board[0][0] == symbol) &&

(board[1][1] == symbol) &&

(board[2][2] == symbol))

return 1;

if ((board[0][2] == symbol) &&

(board[1][1] == symbol) &&

(board[2][0] == symbol))

return 1;

return 0;

}

/*

* Find a win, if any, for the given symbol.

* If a winning square exists, return the square;

* otherwise, return 0.

*/

int find_win(char symbol)

{

int square, row, col;

int result = 0;

/*

* Loop through the 9 squares.

* For each, if it is empty, fill it in with the given

* symbol and check if this has resulted in a win.

* If so, keep track of this square in result.

* Either way, reset the square to empty afterwards.

* After the loop, if one or more wins have been found,

* the last will be recorded in result.

* Otherwise, result will still be 0.

*/

for (square = 1; square <= 9; square++)

{

row = (square - 1) / 3;

col = (square - 1) % 3;

if (board[row][col] == ' ')

{

board[row][col] = symbol;

if (symbol_won(symbol))

result = square;

board[row][col] = ' ';

}

}

return result;

}

/* Choose a move for the computer. */

void computer_move(void)

{

int square;

int row, col;

/* Use first strategy rule that returns valid square */

square = find_win(computer);

if (!square)

square = find_win(user);

if (!square)

square = middle_open();

if (!square)

square = find_corner();

if (!square)

square = find_side();

printf("\nI am choosing square %d!\n", square);

row = (square - 1) / 3;

col = (square - 1) % 3;

board[row][col] = computer;

return;

}

/* Have the user choose a move. */

void player_move(void)

{

int square;

int row, col;

do

{

printf("Enter a square: ");

scanf("%d", &square);

} while (!square_valid(square));

row = (square - 1) / 3;

col = (square - 1) % 3;

board[row][col] = user;

return;

}

/* Loop through 9 turns or until somebody wins. */

void play_game(void)

{

int turn;

for (turn = 1; turn <= 9; turn++)

{

/* Check if turn is even or odd

to determine which player should move. */

if (turn % 2 == 1)

{

if (computer == 'X')

computer_move();

else

player_move();

}

else

{

if (computer == 'O')

computer_move();

else

player_move();

}

draw_board();

if (symbol_won(computer)) {

printf("\nI WIN!!!\n\n");

return;

}

else if (symbol_won(user)) {

printf("\nCongratulations, you win!\n\n");

return;

}

}

printf("\nThe game is a draw.\n\n");

return;

}

To compile and run the code, issue the following command on your Bash shell:

$ clear && make clean && make && make run

Learning how to analyze data in Python with Pandas

NOTE: For this course as discussed in detail in class, each student will individually create their final Python mini project source code repository from this GitHub Classroom link

TBD

Week 12 — Pointers and Data Structures

Week 15

Final projects presentations (Group C project & Individual Python mini-project)