Courses & Projects by Rob Marano

Notes for Week 1

← back to syllabus ← back to notes

Topics

- Software eats the world: Computers, their abstraction, and why we study them – prologue

- Stored Program Concept and its processing

- The alphabet, vocabulary, grammar of computers

1.

1s and0s as the alphabet 2. compute and memory instructions as the vocabulary 3. implementation of compute and memory instructions as the grammar - Introducing the instructions of a computer delivered by the architecture 1. Operations of computer hardware 2. Operands of computer hardware 3. Signed and unsigned numbers 4. Representing instructions in the computer 5. Logical operations

- Performance of computer hardware, and how it is measured 1. ALU 2. Bus width 3. Memory 4. CPU 5. Clock speed 6. Multi-core (Ahmdal’s Law) 7. Threading

- History of computer architecture and modern advancements

Topics Deep Dive

What is Computer Architecture?

Welcome to Computer Architecture! This course will delve into the fundamental principles governing how computers work at a hardware level. It’s not just about programming (though that’s related!), nor is it solely about circuit design (though that plays a role). Computer architecture sits at the intersection of hardware and software, defining the interface between them.

Think of it as the blueprint of a building, like our New Academic Building. Architects don’t lay every brick, nor do they decide how the occupants will use each room. Instead, they design the structure, layout, and systems (electrical, plumbing) that enable both construction and habitation. Similarly, computer architects define the fundamental organization and behavior of a computer system, enabling both hardware implementation and software execution.

Key Questions to Consider

- What exactly is a computer?

- How do we represent and manipulate information within a computer?

- How are instructions fetched, decoded, and executed?

- How is data moved and stored within the system?

- How do different components interact and communicate?

- How do we evaluate the performance of a computer system?

- What are the trade-offs in different architectural choices?

Why Study Computer Architecture?

- Performance: Understanding architecture allows you to write more efficient software and design specialized hardware.

- Innovation: You’ll be able to contribute to the development of new computing paradigms and technologies.

- Problem Solving: You’ll gain a deep understanding of system-level issues and how to debug them.

- Career Opportunities: Computer architecture skills are highly sought after in various fields, from embedded systems to cloud computing.

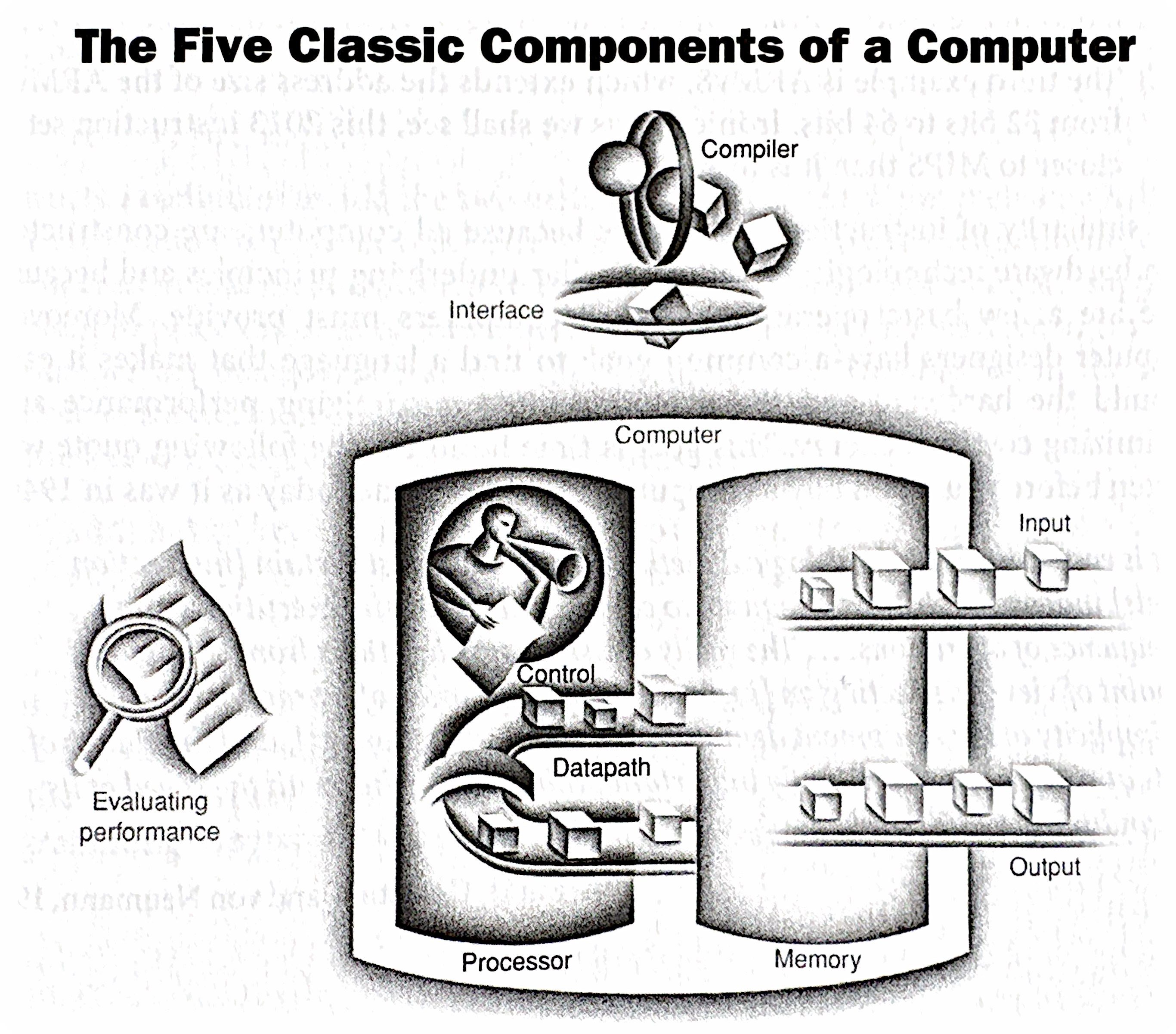

The Five Classic Components of a Computer

Every computer, from your smartphone to a supercomputer, can be conceptually broken down into five main components:

- Input: Mechanisms for feeding data into the computer (keyboard, mouse, network interface, sensors, etc.).

- Output: Mechanisms for displaying or transmitting results (monitor, printer, network interface, actuators, etc.).

- Memory: Stores both instructions (the program) and data that the computer is actively using. Think of it as the computer’s workspace. We’ll explore different types of memory (RAM, cache, registers) in detail later.

- Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU): Performs the actual computations (arithmetic operations, logical comparisons) on the data. This is the “brain” of the CPU.

- Control Unit: Directs the operation of all other components. It fetches instructions from memory, decodes them, and issues signals to the ALU, memory, and I/O devices to execute those instructions. It’s the “conductor” of the computer’s orchestra.

These five components are interconnected by buses, which are sets of wires that carry data and control signals.

The Stored Program Concept

One of the most crucial concepts in computer architecture is the stored program concept. Before this, computers were often hardwired for specific tasks. Changing the program required rewiring the machine—a tedious and error-prone process.

The stored program concept, attributed to John von Neumann, revolutionized computing by storing both the instructions (the program) and the data in the computer’s memory. This allows for:

- Flexibility: Changing programs becomes as simple as loading a new set of instructions into memory.

- Automation: The computer can fetch and execute instructions sequentially without human intervention.

- Efficiency: Data and instructions can be accessed and manipulated quickly from memory.

This concept is fundamental to how all modern computers operate.

IV. von Neumann vs. Harvard Architectures

While the von Neumann architecture is dominant, it’s important to understand its historical context and alternatives.

| Feature | Von Neumann (Princeton) Architecture | Harvard Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Memory | Single memory space for both instructions and data | Separate memory spaces for instructions and data |

| Access | Instructions and data share the same memory bus | Instructions and data can be accessed simultaneously |

| Advantages | Simpler design, more efficient use of memory | Faster instruction fetch, avoids bottlenecks |

| Disadvantages | Potential bottleneck (von Neumann bottleneck) as both instructions and data compete for the same memory access | More complex design, requires separate memory modules |

| Applications | General-purpose computers, PCs, laptops | Embedded systems, digital signal processors (DSPs) |

The von Neumann bottleneck arises because both instructions and data must travel over the same bus to and from memory. This can limit performance, especially when the CPU needs to fetch instructions and data frequently. The Harvard architecture mitigates this by allowing parallel access to instruction and data memories.

(Diagrams comparing the two architectures)

While modern general-purpose computers primarily use variations of the von Neumann architecture (often with caching and other techniques to reduce the bottleneck), the Harvard architecture is still relevant in specialized applications where performance and parallelism are critical.

Additional readings for these architecture types:

Introducing Performance of a Computer

Background reading on performance

Defining Performance in Computer Architecture

Performance in computer architecture is a multifaceted concept, and there isn’t one single “best” metric. It’s often a balancing act between different factors, and the “right” performance measure depends on the specific application and priorities. Here’s a breakdown of key aspects:

1. Execution Time:

- Definition: The most direct measure of performance is how long it takes a computer to complete a task. Shorter execution time means better performance.

- Units: Seconds, milliseconds, microseconds, etc.

- Factors: Clock speed, instruction count, memory access times, I/O speed, and overall system organization all influence execution time.

- Example: Comparing the time it takes two different processors to run the same benchmark program. The processor with the lower execution time is considered faster.

2. Throughput:

- Definition: Measures how much work a computer can complete in a given period. Higher throughput means better performance.

- Units: Transactions per second, jobs per hour, instructions per second (IPS), floating-point operations per second (FLOPS), etc.

- Factors: Processor core count, memory bandwidth, I/O bandwidth, and system software efficiency influence throughput.

- Example: A web server that can handle more requests per second has higher throughput. A supercomputer that can perform more FLOPS has higher computational throughput.

3. Latency:

- Definition: The delay between initiating a request and receiving the result. Lower latency means better performance.

- Units: Seconds, milliseconds, microseconds, nanoseconds, etc.

- Factors: Memory access times, network latency, disk access times, and pipeline stalls influence latency.

- Example: The time it takes for a mouse click to register on the screen is a measure of latency. A lower latency is crucial for interactive applications and real-time systems.

4. Resource Utilization:

- Definition: How efficiently a computer uses its resources (CPU, memory, I/O). Higher utilization (without bottlenecks) can lead to better performance.

- Units: Percentage of CPU usage, memory usage, disk I/O, etc.

- Factors: Operating system scheduling, memory management, and application design influence resource utilization.

- Example: A system that can perform the same amount of work using less energy or fewer CPU cycles is considered more efficient.

5. Power Consumption:

- Definition: The amount of energy a computer consumes. Lower power consumption is often desirable, especially in mobile and embedded systems. Performance per watt is a common metric.

- Units: Watts, milliwatts, kilowatts, etc.

- Factors: Processor architecture, clock speed, voltage, memory technology, and cooling systems influence power consumption.

- Example: A laptop that can run for longer on a single battery charge has better power efficiency.

- Note, the reading above speaks about the “Power Wall.” See below for additional notes on the power wall.

6. Cost:

- Definition: The price of the hardware and software. Performance per dollar is an important metric.

- Units: Dollars, etc.

- Factors: Processor cost, memory cost, storage cost

Sidebar — The Power Wall in Computer Architecture

The “Power Wall” refers to the increasing difficulty and impracticality of continuing to increase processor clock speeds to achieve performance gains. For many years, increasing clock speed was the primary driver of improved CPU performance. However, this approach has run into fundamental physical limitations, leading to the “power wall.”

The Problem:

As clock speeds increase, so does the power consumption of the processor. This increased power consumption manifests as heat. The relationship is roughly cubic: doubling the clock speed can increase power consumption by a factor of eight. This heat becomes increasingly difficult and expensive to dissipate. Think of it like trying to cool a rapidly boiling pot of water; at some point, you can’t add any more heat without it boiling over.

Consequences of Excessive Heat:

- Reliability Issues: High temperatures can damage components and reduce the lifespan of the processor.

- Cooling Costs: More complex and expensive cooling solutions (e.g., liquid cooling) are required to manage the increased heat. This adds to the overall system cost.

- Power Consumption: Higher power consumption translates to higher energy bills and reduces battery life in mobile devices. This has significant environmental implications as well.

- Diminishing Returns: At a certain point, the performance gains from increasing clock speed are outweighed by the increased power consumption and cooling costs. The extra heat generated becomes unmanageable, and further increases in clock speed provide only marginal performance improvements.

The Relationship Between Clock Speed and Power

- Dynamic Power: A significant portion of a processor’s power consumption is dynamic power, which is the power used to switch transistors on and off. This is directly related to the clock speed. Note there is also “static power consumption,” also known as the leakage current to power up transitors. We will deal here only with dynamic power, that is, the power created by switching between 0s and 1s.

- The Equation: Power is that generated when switching between 0 and 1 and the static power: \(P=P_{dynamic}+P_{static}\) where $P_{dynamic} = C * V^2 * f$.

A simplified way to represent this is: \(Power ≈ C * V^2 * f\)

Where:

Cis the capacitance of the circuitVis the voltage-

fis the frequency (clock speed) - The Cube Relationship: Notice that the voltage (

V) is squared in this equation. This is crucial. To increase clock speed, you often need to increase the voltage to maintain stability. This means that the power increases quadratically with voltage. Since voltage often needs to be increased proportionally with frequency, you end up with a cubic relationship overall.

Why It’s Close to a Factor of Eight

- Linear Increase with Frequency: If you only doubled the clock speed and kept the voltage the same, the power would increase linearly (doubling).

- Voltage Increase: However, to reliably double the clock speed, you typically need to increase the voltage. This increase in voltage, when squared, has a much larger impact on power consumption.

- Combined Effect: The combination of the linear increase from frequency and the quadratic increase from voltage results in a power increase that is close to a factor of eight when you double the clock speed.

Important Caveats

- Technology Nodes: As semiconductor technology advances, the relationship between clock speed and power becomes more complex. New techniques and materials can help mitigate the power increase.

- Design Techniques: Architects use various techniques (like clock gating, power gating, and voltage scaling) to manage power consumption and improve efficiency.

- Leakage: In modern processors, leakage current (current that flows even when a transistor is off) also contributes to power consumption, and this can become more significant at higher temperatures associated with higher clock speeds.

In Summary

While not an absolute rule, the “factor of eight” is a good rule of thumb to illustrate the significant power challenges associated with increasing clock speeds. It highlights the need for innovative design techniques and power management strategies in modern computer architecture.

The Shift in Focus:

The power wall has forced a fundamental shift in how computer architects design processors. Instead of focusing solely on increasing clock speed, the emphasis has moved towards:

- Multi-core Processors: Instead of one fast core, processors now have multiple slower cores that can work in parallel. This allows for increased throughput without dramatically increasing power consumption.

- Specialized Hardware: Adding specialized hardware units for specific tasks (e.g., graphics processing units (GPUs), digital signal processors (DSPs)) can improve performance without increasing the clock speed of the main processor.

- Architectural Innovations: Developing new microarchitectural techniques, such as pipelining, caching, and branch prediction, can improve performance without relying solely on higher clock speeds.

- Power-Efficient Designs: Designing processors with lower voltage and more efficient transistors can reduce power consumption.

- Dark Silicon: The idea that not all transistors on a chip can be powered on at the same time due to thermal constraints. This necessitates intelligent power management strategies.

In summary: The power wall is a critical challenge in computer architecture. It signifies the limitations of simply increasing clock speeds to achieve performance gains. The industry has responded by shifting its focus towards multi-core processors, specialized hardware, architectural innovations, and power-efficient designs. Managing power consumption and heat dissipation has become a central concern for computer architects.

Looking Ahead to next lecture — Instruction Set Architecture (ISA)

Today, we’ve laid the foundation for understanding the basic components and principles of computer architecture. Our next lecture will delve into the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA).

The ISA defines the set of instructions that a particular processor can understand and execute. It’s the interface between the hardware and the software. We’ll explore:

- Instruction formats: How instructions are encoded and represented in memory.

- Addressing modes: How the processor accesses data in memory.

- Instruction types: Arithmetic, logical, data transfer, control flow, etc.

- ISA design considerations: How ISA choices impact performance, complexity, and programmability.

Understanding the ISA is crucial for writing efficient code, optimizing compiler design, and designing new processors. It’s the bridge between the high-level world of programming and the low-level world of hardware.